We recommend some of the new arrivals (Books of 2020) to read.

It never occurred to me toward the beginning of this pandemic, when everyone was raising their drawbridges and bringing their blinds down to dig in solo in isolate, that I may make new companions amidst everything. we suggest some good books can give a dependable wellspring of social association even in a period of social separating.

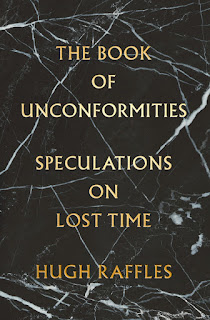

The book of unconformities: Speculations on lost time, by Hugh Raffles.

The anthropologist Hugh Raffles' new book is worried about geography and sadness. It's the history of a couple of eminent stones, including a 20-ton piece of scarred shooting star, mica arranged in Nazi inhumane imprisonments and the layer of marble running under Manhattan.

Between these stories gleams the overwhelming story of Raffles' two sisters, who kicked the bucket inside months of one another during the 1990s. Our faultfinder Parul Sehgal calls it "among the most strange books I've ever perused — a thick, dim star."

The man who ran Washington: The life and times of James A. Dough puncher III, by Peter Baker and Susan Glasser.

This interesting account of the previous secretary of state and consummate insider, who was once called "the most significant delegated official since World War II," uncovers both Baker's achievements and the trade offs he needed to make. "It gives profound knowledge into Baker's qualities at strategy — aptitudes that will turn out to be much more significant as America's impact ebbs in the coming years," Samantha Power writes in her survey.

"Presently particularly, when ineptitude and philosophy have cost the lives of about 200,000 Americans in the Covid pandemic and when confidence in American initiative on the planet has dove, it is difficult to excuse the creators' sentimentality for what Baker had the option to accomplish by moving the apparatus of American governmental issues."

The unreality of memory: And other essays, by Elisa Gabbert.

This assortment of specifically connected expositions, by a writer who is likewise the Book Review's verse editorialist, wrestles with the disorganized and mysterious nature of calamity, even as certifiable emergencies press in from all sides. "Gabbert draws skillful pictures of the exact, uncanny influences that administer our mental relationship to catastrophe," Alexandra Kleeman writes in her survey.

"Considerably more amazing is her aptitude at twisting fresh, clear language into shapes that represent the moving rationale of the unfortunate, keeping the peruser arranged in the midst of constant change."

Payback, by Mary Gordon.

What on the off chance that we sought after vigilante equity on unscripted television? Mary Gordon thinks about this inquiry — and our retributive motivation — in her ethically unpredictable novel about a quite a while in the past wrongdoing and the cutting edge TV have resolved to look for retaliation for it. "Gordon isn't, carefully, a naturalistic or reasonable author, yet rather a moralist, by which I don't mean moralistic," Francine Prose writes in her survey.

"Since her superb first novel … she's fretted about inquiries of morals, conviction, duty, dedication, commitment. What do people owe each other and how might we recognize what is the correct activity?"

Wandering in strange lands: A daughter of the great migration reclaims her roots, by Morgan Jerkins.

This quintessentially American story — following the creator's legacy through subjugation, liberation, multiculturalism and movement — is a hypnotizing update that the partition among Black and white is a bogus double.

"Jerkins makes plain that denying space for Black characters in history is itself an inheritance as American as its unique sins of bigotry and oppression," our analyst, Afua Hirsch, composes. "By investigating the reality of that past with such respectability, this diary enhances our future."

Winter counts, by David Heska Wanbli Weiden.

Justice is rare on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, so Virgil Wounded Horse — the saint of this abrasive, grasping spine chiller — apportions it on an independent premise. Weiden is from a part of the Lakota clan himself, and his book depends on profound examination into its set of experiences and conventions.

"In a tough situation chasing, down-at-the-heels investigators for hire with solid good codes, Virgil must defy numerous impediments immediately," Sarah Lyall writes in a gathering of ongoing spine chillers. "'Winter Counts' is composed with a light touch and a decent arrangement of humor."

The boy in the field, by Margot Livesey.

In Livesey's perfect new novel, three kin on their route home from school discover a kid who has been assaulted and left for dead in a field. This revelation prompts a puzzle that will change the lives of all included.

"Livesey's composing hushes up, perceptive and delightfully productive — there's not an additional word or scene in the whole book — but then at the same time so artistic, you can hear the symphonic soundtrack as you tear through the pages," Jenny Rosenstrach writes in her survey.

Comments

Post a Comment